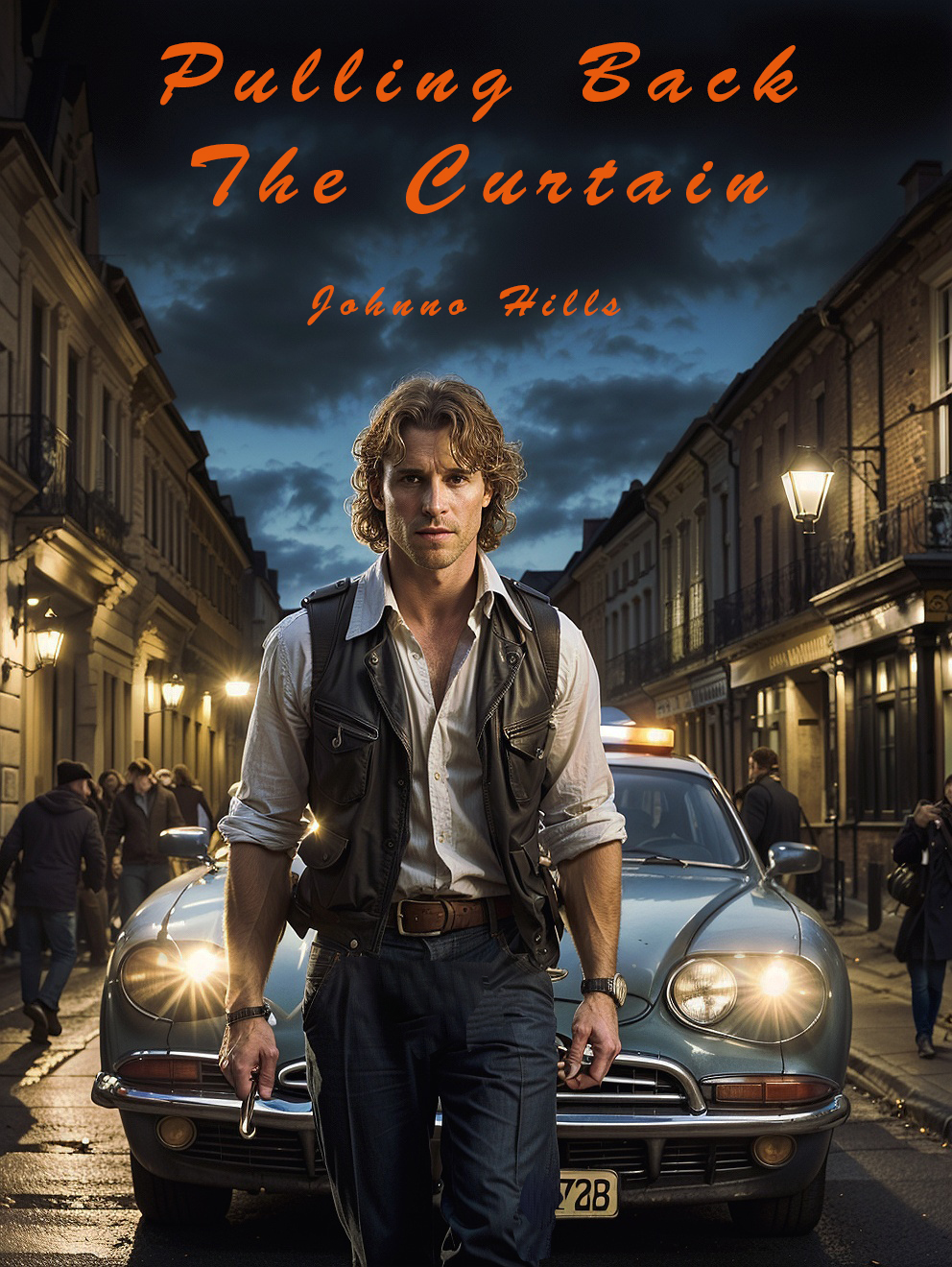

Pulling Back The Curtain - Book

So, the last year of the 1980s, and my seventeenth year of birth, began with the sudden death of my father from a heart attack, or “myocardial infarction”, as stated on his death certificate. Dad's death marked the first time I'd experience the loss of someone close to me, or, at least, someone in close proximity to me. He and I would never be bonded emotionally and our relationship remained, for the most part, an adversarial one. We couldn't relate to each other, had very little in common during our time in each other's respective lives, and, in his eyes, I would always represent a perpetual barrier to his securing his wife's undying love and fidelity. Lacking any real emotional intelligence, Dad simply didn't have the psychological wherewithal to understand my mother's behaviours and manage them appropriately. If, towards the end of his life, he figured out how incapable she was of loving him, he didn't reveal this and his love for and belief in her as the only one to satisfy his needs suggested otherwise. Therefore, I suspect he died in ignorance of her inability to either love anyone else or express love in positive and meaningful ways. In reality, whatever she had to give was always conditional and, upon reflection, really not worth having.

Prompted by Dad's sudden absence, I found myself attempting to reconcile the expected and accepted expressions of bereavement with my deeply rooted feelings of hatred and disconnection. Having reflected on my outward expressions of emotion at the time of dad's death, I realised my tears were those of shock, and, to some extent, relief, rather than those born out of grief. His passing would not lead me to romanticise about our relationship and revise it into something better than it was and I can't admit to having been sombre in mood for too long before adopting the role of surrogate father for my eleven-year-old sister while providing some comfort to my superficially grieving mother. Yet, time and experience has enabled me to view my father slightly less unkindly and recognise my own gratitude for those ways in which I actually take after him. However, it'd be another eight-and-a-half years before I'd feel the kind of profound pain associated with death. This would come following the deaths of two people who died within two months of each other, one whom I never met and the other I'd never have expected to meet.

Meanwhile, at the age of sixteen, I found myself eager to discover where I fitted in and where I could truly enjoy and learn about life. In seeking the kind of pleasure and adventure born of youthful exuberance, having to experience the pain of life didn't occur to me at all. Nor did I understand my mind and body sufficiently at that time to realise how I had been, and would likely, respond in the future in certain environments and situations. I knew nothing of the wolves that had already begun sniffing at my door. They would continue to do so at regular intervals throughout my life and wreak havoc in my personal relationships until I could understand how to bring them under some control. However, without realising it, I'd already started to learn to be me although it wouldn't be too long before events conspired to test my character to the full and teach me about the kind of person I was, and would, become.

Those who knew me as a child, and then as a teenager, would rightly regard me as a number of things, depending on their interactions with me. To some, I was the fool, the joker, the class comedian and always up for a laugh. To others, I was cocky, an attention seeker, a tormentor, and a kid with a huge chip on his shoulder. While failing to recognise the chip at the time as being exactly that, I realise in retrospect how easily roused I was to anger. I couldn't have expected much else given the environment in which I grew up, where my parents were unable to observe proper boundaries and take responsibility for their behaviour but expected their children to do just that, despite the lack of good example and everything to the contrary. The injustice of their hypocrisy would influence all my future relationships, both private and professional. Not only would it put me on constant guard against anyone remotely similar in character, it also set me on a number of collision courses with those similarly negligent in their responsibilities. Furthermore, it ensured that any semblance of a relationship with my mother became, and remained, as fractious and combative as that with my father. So, at this point in time, I had a conflict to resolve between my mother's self-exonerating assertions that we moved home so many times because I upset the neighbours, and that it was my behaviour towards my father that ultimately killed him, and my belief that I couldn't be the bad person she said I was. In truth, we moved so often on account of my mother's depression and her misguided belief she'd be happier, or less unhappy, elsewhere, coupled with the stream of County Court judgements that landed periodically on our door mat. As for what killed my dad, his death certificate made no mention of my behaviour! Therefore, I had to go out into the world in search of second opinions in order to learn about life, learn about me, and find out who was right and who was wrong.

The desire for fun and adventure in the early 1990s led me into a string of casual jobs, house moves, and both casual and lifelong relationships. In the summer of 1989, I began working as a terribly ill-prepared second chef at a local Brewers Fayre pub called 'The Horseshoes', in East Farleigh, another sleepy rural village located in the south of Maidstone, next to Coxheath, the village where I spent six years of my childhood. With my formal education having ended following our move to Malta in July, 1986, I felt at somewhat of a disadvantage having no formal qualifications when applying for jobs, and landing a post at 'The Shoes', as it was known to locals, would not be the last time I'd have to blag my way into a job and trade on personality or previous experience rather than qualifications. Thankfully, some of the kids I'd known from school already worked there so it was good to see some familiar faces. One particular face belonged to my table-tennis buddy, Michelle, who I'd met at the playscheme held for local kids at Coxheath village hall in the summer holidays. Michelle was also in the same class in junior school as my elder sister, Dee. Sporting golden locks, thick eyelashes, a generous pout and an attitude that gave off intimidating “don't fuck with me” overtones, I found myself instantly drawn to her. Her boldness and inclination to speak her mind dovetailed perfectly with mine. Delving a little deeper, and after having spent some time with her and her loving parents, I realised how they'd nurtured her with the kind of responsible and wholesome parenting that led her to become the honest, steady, and dependable woman I still know her as to this day. To me, she represented boundaries and stability, something my life had lacked, which further drew me to her. Her presence in my life provided something of an anchoring influence, a beacon in those moments during my life when I felt I'd lost my way, or couldn't feel that I'd lost myself.

In complete contrast, an additional significant influence around that time came courtesy of another female, albeit someone almost thirty years my senior. While not her real name, I shall refer to this free-spirited force of nature as “Shirley”. The combination of her overly wrinkled skin, nicotine stained teeth and darkened roots emerging from beneath her short, peroxide- blonde hair, made her appear older than her forty-eight-years. However, at heart, Shirley remained a good time gal who loved her family, her fags, her friend's home brew cider, and, especially, her men!

Shirley lived on a council estate outside of Maidstone, named Parkwood. While Parkwood didn't have the worst reputation of all the council estates around Maidstone, it was a place where I would never have expected to live. However, needs must, and, having fallen out once more with my own mother, I found myself renting a room in a council house from someone almost ten years her senior. Moving to Parkwood also meant living among some rather unsavoury characters, two of whom were Shirley's prodigiously law-breaking sons. Specialising in commercial burglary and narcotics, within days of meeting Shirley's elder son, he asked me to drive him to a friend's place over the other side of Parkwood. I found this a little odd, as the flat we ended up in was well within walking distance. Nonetheless, I'd just bought my first car, a mark II Ford Escort, from a friend, and needed no excuse to take my new wheels for a spin. Yet, what spun me round was what happened shortly after we arrived. No sooner had we both walked into the kitchen than both Shirley's son and his friend began frantically applying tourniquets to their arms, and then, right before my very eyes, began shooting up what I came to realise was heroin. Not long after, her other son left me similarly speechless and wondering what kind of situation I'd got myself into. Having also recently made his acquaintance, I joined him one particular day for a casual stroll through the alleyways of Parkwood towards the local shops. Emerging from the alleyway, we wandered towards a rather non-descript looking white van which lay between us and the parade. No sooner had we reached it, and with me obliviously mid sentence, Shirley's son produced a baseball bat concealed down the leg of his jeans, and, with one almighty thwack, proceeded to put the back window in, sending shattered glass flying in every direction. Then, he casually returned the bat to its hiding place, sniffed the air and proceeded to rejoin me in conversation. To this day I don't know why he did this and Iwas too stunned at the time to ask. Somebody had obviously crossed him. Following the van incident, this particular son would go on to steal from me, relieving me of my Philips twin-deck tape player and some pre-recorded VHS tapes.

Incidentally, despite having lied, cheated and stolen her way through most of her life, my mother would've looked down on Shirley and her sons for the fact that they lived on a council estate, regardless of their criminal exploits. She wouldn't deign to live in a council house herself, something her own cruel mother would mock her for, although my grandmother's hypocrisy would not be lost on me, and I suspect she wouldn't have deigned to live in one, either. In hindsight, there was very little difference in their respective behaviours except their socio-economic background and the conspicuousness of the crime. Interestingly, this would not be the last time I'd encounter similarly chaotic characters embroiled in a life of spiralling crime and

substance abuse, albeit in an entirely unexpected capacity.

Having taken another cheffing job at a pub a couple of villages away from Parkwood, my new car came in handy for getting me to and from work. However, before long, I realised that I'd bought a bit of a dud and the money I'd have to spend on it, coupled with my poor budgeting skills, meant my outgoings exceeding my incomings, and I soon struggled to pay my rent. Confiding in Shirley my predicament, the naivety of my nineteen years was such that I didn't anticipate her suggested solution. Instead of what I had expected, an offer to perhaps slightly lower my rent, or stagger payments, Shirley suggested I pay as much as I could in addition to which we could have sex. Under different circumstances, the prospect might have terrified me, however, Shirley and I had already developed a connection and struck up a good friendship, one based primarily on a mutual enjoyment of adventure, humour, fun and pleasure. We found ourselves indulging in various childish pranks, the more outlandish of which involved me removing my velcro side-fastening underpants in supermarkets then placing them on the checkout conveyor belt, along with our other purchases, and watching them inch towards the unsuspecting cashier, while engaging each other in deep conversation, but always with one eye on the reaction of the cashier, who would glare at them with a confused and horrified look on their face. I would chance my arm with a similar prank at that time when Michelle and I went with a group of other friends from 'The Shoes' to the local cinema to see the Arnold Schwarzenegger film, Kindergarten Cop. On this occasion I decided beforehand to cut the rear pockets out of my jeans and, except for the denim strip down the middle and wearing no underpants, completely exposed my bare buttocks. Upon them realising what I'd done, our group then splintered, with half too embarrassed to come to see Kindergarten Cop (so instead they went to see Rocky 5), leaving Michelle and I to see Kindergarten Cop as originally intended. However, Michelle, at the time, did not see the funny side and insisted we let everyone else in the cinema go before we attempted to leave. How I managed to make it through that night without having ten bells kicked out of me, I'll never know.

While it seemed like fun at the time, it's not exactly something I look back on with pride. I'd pull a similar supermarket stunt (what was it about supermarkets?) on poor beleaguered Michelle each time we stood at a checkout and I'd ask her, casually, but in a voice loud enough for the cashier to hear, whether her boyfriend still liked to eat her pussy, before watching her crumple into a mortified mess. Amid all the hilarity, Shirley's daughter, then in her late teens, would also be on hand on one particular occasion to provide a moment of supreme comedy gold. Having arrived home from the pub on a split shift and eager to get some shut-eye, I greeted Shirley and her daughter, who were cheerfully chatting away in the kitchen while chopping vegetables for their home-made pizza. They much preferred to buy a pizza base and create their own toppings. Leaving Shirley to sprinkle her grated mozzarella and her daughter to slice some chillies, I retired to my bedroom, and, after closing the curtains, soon fell asleep. The next thing I knew, I awoke to the sound of Shirley's daughter screaming at the top of her lungs in the bathroom opposite my bedroom, followed by the sound of frantic pounding on the floor, as if she were doing some kind of crazed war dance which was then followed by the sound of the shower tap being turned on full blast. Once the screaming had subsided, I stumbled back to bed, only to learn subsequently that Shirley's daughter had dashed to the bathroom to change her tampon. In the rush to insert a fresh one, she forgot to wash her hands after cutting up the chillies for their pizza and by the time she realised she was onto a loser, it was too late...

So, in response to Shirley's proposal, despite being fully comfortable with my nature and attraction to my own sex, it didn't seem unnatural to me to try and enjoy sex with Shirley, which we did on a regular basis. While it didn't fulfil me in the same way as the sex I'd enjoyed with men, both before and since, Shirley made it fun and exciting, even recruiting the son of a former friend, with him being a year or two older than me, into my first experience with group sex. Having overcome my financial difficulties and managing to save up enough money for a three month return ticket to California, I'd leave Shirley's in mid 1992. We'd see each other again from time to time upon my return until she then settled into a permanent relationship with someone nearer her age. With Shirley I got to indulge a wild and rebellious side to my character that I couldn't with Michelle. What I had with Shirley was fun but fleeting, and what I had with Michelle was profound and enduring, even during those times when distance became a barrier to regular face to face contact, as America would feature in my life again in the not too distant future.

Then, in late 1994, I found myself back in Lee in South-East London, where my life began almost twenty-two years before. By this time I'd already left catering for a career in hotels and a new job in the city. Owned at the time by the Stakis hotel chain, and in all it's towering red-brick Victorian grandeur, London St. Ermin's Hotel stood proudly at the end of a cul-de-sac around the corner from Buckingham Palace and Scotland Yard. Opening as a hotel in 1899, the frontage of the Grade II-listed St. Ermin's resembled that of the legendary London Savoy Hotel, with its drive in and out courtyard. St. Ermin's could make its own impressive claims to fame, having been built upon the site of a 15th century chapel, where in 1940 Winston Churchill held a historic meeting to establish a 'Special Operations Executive', which formed the basis of the SAS. MI6 were also stationed for a time in the hotel, which, according to folklore, also concealed a secret passage which ran from behind the hotel's grand staircase directly to the House of Commons.

Being the company's flagship branch, St.Ermin's became my hotel of choice on account of my having tended bar at its sister hotel in Maidstone. I underwent an internal transfer from Maidstone to St. Ermin's, first, as a receptionist, then as a night auditor. While a diminutive Asian fellow by the name of Wan Cheah, who always walked with his head tilted to one side, oversaw operations in Maidstone, the redoubtable trio that were General Manager, Mr. Wakeford, Deputy Manager, Mr. Giauna, and Front of House Manager, Mrs. Harlow, ran a tight ship at St. Ermin's. With reception falling under Front of House, I reported to Mrs. Harlow, and had more to do with her than Messrs Wakeford and Giauna. With her finely-tailored navy blue blazer and matching blue tartan pleated knee-length skirt, Mrs. Harlow dressed for, and meant, business. Despite being no older than mid thirties, with her air of mild disdain, Mrs. Harlow struck fear into the hearts of all who worked under her. In manner of my friendship with Michelle, Mrs. Harlow's strict school headmistress demeanour and no nonsense approach to her work drew me instantly to her. She too represented boundaries and as much as I'd often taken pleasure in testing boundaries, I knew she was not to be trifled with. However, finding ready favour with that pied-piperess, I soon joined Mrs. Harlow's merry band of queers, along with Richard and Thomas, the morning-suited hotel Club butlers. Being both expertly trained in their craft, Richard and Thomas's skills were in high demand and they could go anywhere they wanted, which they did at the end of 1994, when both left St. Ermin's to take up posts as butlers at the exclusive five-star deluxe Lanesborough Hotel on Hyde Park Corner. At that time, The Lanesborough housed the most expensive hotel suite in England.

Although now living back in Lee, where I spent the first seven years of my life, meant being close to my elderly relatives on my father's side of the family, while acquaintances were in ready supply, good friends were not. That made an unexpected knock at the door of the staff house one night from Tracy and Debbie, a couple I''d befriended at the Maidstone hotel, such a welcomed surprise. Equally unexpected was their suggestion that they take me, for my first time, to a gay bar. At the tender age of twenty-one, I guess I was something of a late-comer to the scene. This was due to a combination of indifference to the scene itself, a lack of such venues in or around Maidstone, and, importantly, no other gay friends, before Tracy and Debbie, with whom to hang out. However, with The Gloucester public house, on the edge of Greenwich Park, but fifteen minutes away by car, before I knew it, we'd pulled up outside. Not knowing what to expect beyond gaudy décor, effeminate men and butch lesbians, once inside, I saw the kind of well-worn red velvet seats and red paisley carpet characteristic of most saloon bars in public houses across the country at that time. There was also nothing particularly conspicuous about the patrons, either, with the majority dressed in suits with loosened ties contrasting with those appearing casually in jeans; nothing that resembled the derogatory stereotype I myself held and to which I felt I really could not relate.

My second outing would really open my eyes, and, again, with Tracy and Debbie, saw us venture into central London one Monday night to a club in the huge basement of the London Astoria, opposite the Centre Point building on Charing Cross Road. Constructed in the shape of an arena and built on two levels, the upstairs of the LA2 consisted of a bar on one side and a viewing gallery on the other, while downstairs was situated an enormous dance-floor separated into two parts by a large catwalk. As we sipped our drinks, I peered inquisitively through the glass and down to the dance floor. There in the dark, a few solitary figures had already taken to the floor. Dancing with complete abandon, and seemingly oblivious to the gaze of others, they moved with confidence as the track 'Love Eviction', by House music outfit Quartzlock, blasted out across the floor and into the abyss. I'd never seen anything like this in my life and found the enormity of it all somewhat overwhelming, not to mention intimidating. I'd also never seen anything like the characters that started steadily streaming in, from lace-up knee length boots and chaps in cherry red Doc Martens, short pleated tartan skirts and denim jackets, to full-blown Marie Antoinette drag complete with powdered wig.

As the LA2 came to exuberant life, I sat demurely in my black trousers, white shirt and black waistcoat, looking like I'd just come off the late shift at Cafe Rouge. My bottomless antics in Maidstone aside, I pondered as I started at the revellers below exactly how I'd fit in with the kind of ostentatious and pretentious characters I saw before me, if they were a typical example of London gays. I didn't feel the inclination to blur the lines of gender expression at that time in addition to which I was just beginning to learn how to enjoy manhood and dressing as a man would typically dress. That said, I would learn in time to think more critically about the issue of self-expression, what it meant to be a man and the kind of man I wanted to be. For now, I didn't feel the LA2 was for me, preferring something a little more intimate, less pretentious and with a smaller crowd. Indeed, it wouldn't be too long before I'd fine two such lower key venues, a rather dingy but friendly below ground bar on St. Martin's Lane in Covent Garden called The Brief Encounter (aka The Brief), and The Phoenix on Cavendish Square, to hang out of a Friday and Saturday night whenever my work rota allowed.

Curiously, approximately eighteen months later, it would be at The Brief Encounter where an altogether unexpected encounter would lead to a rather longer-term encounter, taking me on an overseas adventure which would end up changing the course of my life. However, the build-up to one of the greatest experiences I'd have up until that point in my life also lay elsewhere. That meant moving on from St. Ermin's after only seven months. Regrettably, it would also mean saying goodbye to the venerable Mrs. Harlow. I never did get to call her by her first name, Caryl, although one of my most endearing memories of her was the prominent gap she had between her two front teeth. I've absolutely no doubt though that she still runs a tight ship, wherever she may be. So, feeling hungry for a bigger and tastier piece of the London hotel pie as I was, in April, 1995, I followed where butlers Richard and Thomas led and headed to the exclusive The Lanesborough Hotel on Hyde Park Corner to be their new night auditor.

In the chill of the March night air, sweat continued to trickle down my face. Nerves undoubtedly played a part, however, the main reason for sweating so profusely was the route I'd taken to reach The Lanesborough for my first interview. Despite being born in Woolwich, up until now, in March, 1995, I'd spent very little time in Central London, with the exception of my travels to and from St. Ermin's and the LA2. So, having ended my journey at Victoria Station, I jumped on the tube and then got off at Oxford Circus. Once above ground, I headed westward along Oxford Street then turned left down Park Lane, where I believed I'd find The Lanesborough situated at the bottom. Passing the famous Dorchester and London Hilton hotels on my left, I looked into the distance to see the twin flames of the torches above The Lanesborough's main entrance flickering in the wind. Being unsure of exactly where I was going, I'd left my home in Lee in plenty of time for my interview at 10.30pm with the hotel's Front of House manager, a man by the name of Michael Naylor-Leyland. I'd never met anyone with a double-barrelled name before, but it sounded like he must be very well-to-do. I'd also never had an interview that late before. However, as I'd applied for the post of night auditor, both my first and second interviews would be at night, followed by two further interviews on separate days.

Sitting down at the bus stop outside The Lanesborough, I glanced at my watch. Despite taking the long way around, I still arrived with plenty of time to spare. As the M People album, Bizarre Fruit, playing on my Sony Discman, I turned around to survey the hotel's awesome edifice. Resembling a Greek temple, four large cream coloured stone pillars at the hotel's entrance, two on one side and two on the other, supported an entablature upon which was engraved the hotel's name. The flames of the two torches, each at opposite ends of the entablature, danced in the wind. Situated on Hyde Park Corner, The Lanesborough sits opposite the Wellington Arch, with the eastern side of the building overlooking the arch and the gardens of Buckingham Palace. Having been the former St. George's Hospital, as a hotel, The Lanesborough opened on New Year's Eve in 1991. Although the royal family of Abu Dhabi owned the building, Texan oil heiress Caroline Rose Hunt owned the business as the founder of Rosewood Hotels and Resorts. Rosewood Hotels held an impressive portfolio of luxury resorts all around the world, from London to Paris and from Dallas to Beverly Hills.

With the cool breeze having dried most of my face yet with no tissues to hand to dry off the rest, I turned over the cuff of my black bolero jacket and dabbed away the little sweat that remained the headed towards the hotel. Pushing open one of two heavy oak doors, as I stepped in, the sight of more cream coloured fluted Corinthian columns and a cream marble floor patterned with black squares met my eyes. I approached the hotel's twin reception desks where a tall, thinman in a morning suit busied himself plumping up the cushions of the four chairs split between two ornate glass-topped tables. Announcing that I'd come for an interview with Michael Naylor-Leyland, the man looked me up and down, glared at my bolero jacket, my beloved bolero jacket, and informed me he was Michael Naylor-Leyland. While not sounding overly well-to-do, Michael Naylor-Leyland, or MNL as I would often hear him referred to thereafter, had an air of charm and suaveness about him. Leading me away from the main reception and into a room off the hotel's library bar, called the Withdrawing Room, I gained a better look at MNL's brown hair, with flecks of grey, in a kind of shortened mullet style. Despite his seeming disapproval of my choice of jacket, I seized the opportunity to redeem myself when a staff member interrupted the interview and reminded MNL to ring Saskia when he'd finished. In an attempt to curry favour, I mentioned to MNL the coincidence that I had a younger sister named Saskia, to which he explained that Saskia was his wife. So, my apparent fashion faux-pas notwithstanding, and for which I'd be gently mocked by future colleagues, I'd passed my initial interview. I would also pass the

second, which took place this time with the night manager, an elegantly tuxedo-clad man by the name of Lawton Price. My third interview took place during the day with the head of Human Resources, a rather stern lady called Ann France. Making me work hard for my place at the hotel, and stating repeatedly that she didn't understand why I would want to work at The Lanesborough, (notwithstanding the fact that the hotel was a 5-star deluxe hotel while St. Ermin's was a mere 4-star), I would learn subsequently that the night audit post had been promised to a waitress in the Conservatory restaurant. However, Lawton wanted someone with night audit experience and something of a stand-off ensued between Lawton and Ann France,

which, thankfully, Lawton won. My final interview took place with Mr. Gelardi, the hotel manager. Unbeknown to me, if you were fortunate to make it to an interview with Mr. Gelardi, that invariably meant you got the job, an audience with Mr. Gelardi being a mere rubber-stamping exercise. To say after four interviews that I felt relieved would be an understatement. I swore it would've been easier to get into Fort Knox!

Securing a job at The Lanesborough also meant having to find alternative accommodation and moving away from Lee. So, around this time I took a single room in a shared terraced-house on Davisville Road in Shepherd's Bush in West London, between Stamford Brook and Ravenscourt Park tube stations on the District Line. Consisting of a single-bed, a single wardrobe, a fridge and a wash basin, my room appeared sparse and pokey. Curiously, it also had its own electric meter which gobbled up pound coins. With the bed lacking a headboard, I dragged the fridge to one end of the bed and against which I rested my pillows. I never saw any of my housemates. What with me working nights, and, presumably, them working days, we truly were like ships passing in the night. Not long after moving in, I also registered with the local GP surgery. Thank goodness I'd only have to go there the once. This occurred following an ill-conceived attempt to remove the hair from my scrotum. Mistaking the length of time I should keep the hair removal cream on, and after doing so for too long, I would later suffer an adverse reaction. Waking up the next day to an extremely painful and shrivelled scrotum that had morphed overnight from a

perfectly smooth sack into something resembling the texture and appearance of an ugli fruit, in complete desperation, I booked an emergency appointment at the new doctors. With my humiliating predicament revealed in full, the doctor packed me off to the chemist in short order. Closing the door as I went to leave, suitably embarrassed and with prescription in hand, I heard the doctor let forth a rampant burst of laughter. Oh, well, c'est la vie!

Travelling to my new job also meant a daily ride on the tube. In the main, I'd walk to Stamford Brook and pick up the District Line eastbound before changing at Hammersmith. From there, I'd jump on the Piccadilly Line to Hyde Park Corner. What would certainly not be lost on me, even on my first night, was the difference between the sight before me while working my way up from the underground and where I'd find myself approximately twenty-minutes later. The smell of sweat and stale urine in the air coupled with the plight of the street homeless bedding down in the tunnels and walkways under Hyde Park Corner contrasted sharply with the image above ground of international celebrities, multinational CEOs, bottles of Bollinger and trays of petit-fours. Indeed, the summer of 1995 would transpire to be a hot one and the stifling temperatures intensified the pungent odours of the London Underground.

In between work, that summer would see me begin to develop something of an active social life. When not at work, I'd head into town to meet the casual friends I'd made at 'The Brief', where we'd hang out in the dim light of the downstairs bar, strutting around to the dance tracks of the day, courtesy of resident DJs Glen and Orlando. Otherwise, when I wasn't working of a Friday or Saturday, we'd start off at The Brief then head to Cavendish Square, behind Oxford Circus, to another downstairs club called The Phoenix. Introduced to The Phoenix by a waiter at The Lanesborough, I found it's intimacy and unpretentiousness instantly appealing and it became, for me, a happy place. Sporting my new cherry red DMs, white jeans and Mexican-style bandana, I'd head over to The Phoenix with my mates from The Brief where we'd tear up the tiny dance floor to such cheesy summer bangers as 'Sunshine After the Rain' by Berri, 'Santa Maria' by Tatjana and 'Sky High' by Newton. My energy was such at that time that I'd wake up early between night shifts and meet my deputy night manager, Tristan, for a game of tennis near his home in Wandsworth. I'd also meet some of my Lanesborough colleagues in Hyde Park in the late afternoons to play softball against other hotels in the area before convening in Shepherd Market in Mayfair for a few drinks. From there I'd go on to the hotel to work my night shift. Towards the end of that year, I'd find myself going to The Brief for a few drinks and meeting my friends there before heading to The Lanesborough to start work. By this time, I'd also finally grasped how to tie a full Windsor knot, something I'd struggled to learn to do and in which I'd often have to enlist the help of Tony, the night butler, on those occasions when we happened to be in the changing room at the same time.

Ever since its opening as a hotel in 1991, the twenty-four hour butler service set The Lanesborough apart from the other top class hotels in London, while at a cost of £3,500 per night, the hotel's Royal Suite became the most expensive hotel room in England. For the price tag, guests could expect a suite which took up half of the second floor of the hotel and with a commanding view overlooking Wellington Arch and the gardens of Buckingham Palace, in addition to their own 24-hour butler and a chauffeur driven Bentley. As a night auditor tasked with shutting down IT systems, checking room rates, pulling reports for the accounts department and resetting systems for the next business day, most of my work took place behind the hotel

reception and out of the way of guests. There, dressed in my morning suit, I'd answer the hotel phones, taking both internal and external calls. This I would do until things quietened down, usually around 1am, by which time I could begin my audit.

Not long after joining the night crew, I found myself tasked with training a chap named Daniel, a management trainee a few years younger than me, on the night audit element of his management trainee program. At the outset, it became clear that training Daniel would be no easy task, as he seemed more intent on star-gazing and hob-knobbing with the rich and famous at the reception desk than coming to grips with the rigours of the night audit. So, I did my best to persevere with my younger charge's intermittent dashes into the back office to announce that he'd just seen Christopher Walken, or Lionel Ritchie, or Michael Bolton. On my part, I did my best to steer clear of the higher profile guests and was largely successful in this, with the exception of two who were, at the time, among the biggest stars in the world. Throughout their stay in December, 1995, one of them would be the cause of innumerable headaches, while the other, visiting two months later in February, 1996, left me with the kind of memory I still hold dear to this very day.

Given the hotel's reputation for class and grandeur, it seemed a forgone conclusion that the Christmas tree that year would be something special. Festooned with silver bows and an array of elegantly wrapped boxes piled up underneath, the plump ten-feet-tall fresh-cut tree stood proudly opposite the hotel's twin reception desks. Erected in the first week of December, the tree's appearance would coincide with that of a very special guest. The arrival of this guest would herald the one and only time I'd ever be chastised by Tristan. Following the departure of Lawton Price a few months after I joined night audit, as Lawton's deputy, Tristan took over the role of Night Manager. An altogether amiable man in his late 20s, Tristan made for a competent and experienced manager and, being tennis partners too, we enjoyed good interaction both in and out of work. All that changed one night during the week the Christmas tree appeared. What made this particular night a memorable one, and for all the wrong reasons, was the arrival of international superstar, Mariah Carey.

Mariah Carey's trip to London to promote her 'Daydream' album culminated in an autograph signing at Tower Records in Piccadilly on 7th December. Despite my reluctance to leave the relative safety of the back office, I joined the other available members of the night team to form a welcome party for Miss Carey, who was due in around 11pm by private jet. We assembled behind the two large oak doors which we kept closed in order to shielded ourselves from the chilly December night air. Having turned the phone's ringer up so I could hear it from the main doors, I dashed to and fro several times during the next two hours to answer calls before rejoining the night staff in what had become by now weary anticipation. Just then, a large black car roared into the hotel driveway following which a large group disembarked. As we held the doors open, a young blonde-haired lady backed in clutching a Handycam. Following her camera-toting assistant, who continued moving slowly backwards, in skipped the renowned Miss Carey, wearing black knee-length boots, like the ones I'd seen at the LA2, complete with black leggings and black cropped skin-tight jacket. No sooner had she spotted the Christmas tree than she skipped towards it, remarking that the presents beneath it must all be for the staff. Not so. In fact, our Christmas present that year would be a plush white bathrobe, the kind of which were to be found in the guest's rooms. However, our bathrobes would have 'The Lanesborough, London, 95', embroidered on the chest pocket. Skipping away gaily following her remark about the presents, Miss Carey headed for the hotel lifts and, as quickly as she arrived, she'd gone.

With all eyes on our world famous guest, I hadn't noticed a man come in after her and who now sat at the reception desk. This man I would learn was Mariah Carey's then manager, a man by the name of Randy Hoffman. Returning to the back office, I couldn't help but overhear Mr. Hoffman as he briefed Tristan as to a major change in procedure regarding calls to the Royal Suite, where Miss Carey would be staying for the next few days. Most high profile guests who stayed at the hotel relied on a pseudonym which would appear on the hotel guest list and would be given to external callers in order for the telephonist to safely connect the call. Miss Carey's pseudonym, I had been briefed beforehand, was Maria Beasley. I had also been told that under no circumstances was I to put any calls through to the Royal Suite unless the caller asked for Maria Beasley, or M. Beasley. Randy Hoffman explained to Tristan that the pseudonym was now being changed from Beasley to Hoffman and only callers asking to speak to Maria Hoffman, or M. Hoffman, should be put through to the Royal Suite. Tristan then came into the back office and explained the change to me. As soon as he left, I began my delayed night audit.

No sooner had I started than the phone rang. On the other end of the line, an abrupt sounding man with an American accent asked to speak to Maria Beasley. When I advised the man that we had no guest in the hotel by that name, he exploded. Yelling at me down the phone that he knew Maria Beasley was staying at the hotel, he demanded I put the call through. Suddenly, I felt hot and began to panic. However, my courage rose and I repeated to the man what I'd told him before. With this, the line went dead. After having calmed myself down, I continued with my night audit, mulling over the thought that perhaps I'd spared Miss Carey from the inconvenience of a nuisance call. Justt then, Tristan came flying into the back office and

marched up to the other side of the table where I sat with my reports all spread out. Appearing even hotter and more harassed than I must've looked a few minutes earlier, Tristan proceeded to berate me for having upset Tommy Mottola, from whom it seemed clear, Tristan had just been on the end of an ear-bashing. Ignorant of this Tommy Mottola and not aware of having been rude to anyone, I became instantly defensive and told Tristan I had no idea what he was going on about. While attempting to calm things down, Tristan explained that Tommy Mottola was in fact the CEO of Sony Music Entertainment and the husband of Mariah Carey. Still puzzled, I explained that I hadn't spoken him, at which point Tristan revealed that he'd phoned in just now asking to be put through to the Royal Suite. With the misunderstanding now becoming a little clearer, I explained that a man did call in asking for Maria Beasley, however, as the pseudonym had been changed to Hoffman, I didn't put the call through as per the change of instructions from Randy Hoffman. Never one to allow myself to be bullied, I pointed out to Tristan that had I put that call through and it had turned out to be a bogus caller, I'd be in the kind of trouble that could potentially have cost me my job. After all, it wasn't my fault that Tommy Mottola hadn't been made aware of the change of pseudonym, and, having defended myself vigorously to Tristan, I returned to my night audit, leaving him in no doubt that now I was the one who was pissed off.

I wish I could say that this incident was the beginning and the end of it all, but I'd be lying if I did. The difficulty continued a few nights later when Miss Carey called the phone of the in-room dining waiter to place a food order. If the waiter, at that time a good-natured Dutch fellow by the name of Lambertus, was away from his desk, the call would divert to my phone in the back office. Being something of a creature of habit, I tended to take my lunch in the staff canteen around 3am each night. Yet, on the night in question, my plans for lunch would be scuppered when I went to head down to the staff canteen and a diverted call from the Royal Suite to Lambertus's phone came through to me. Answering the call, I recognised the voice of Miss Carey instantly. I apologised that she hadn't been able to reach in-room dining and asked her if she would like to leave her order with me and I'd deliver it to the waiter immediately. With that, she proceeded to reel off a food order that would've fed a small army, and, not wanting to upset her too after the Tommy Mottola debacle, I told her that I would ensure she received her order as quickly as possible. Dissatisfied with my response, she asked me exactly how long that would be. Reluctant to give an exact time for fear it would turn out to be wildly inaccurate, I wilted under pressure and said the order would be with her in about half an hour. After voicing her displeasure at the delay, Miss Carey hung up. Without a second to lose, I flew downstairs and handed over the enormous order directly to the only chef we ever had on at night and wished him the best of luck. Poor Lambertus. I'll bet he copped an earful!

Another source of frustration during Miss Carey's stay would be the additional work involved for back office staff. At this time, she was one of the biggest recording artists in the world and had travelled to London with a huge entourage. She also received a significant number of calls into the hotel from the United States. Ordinarily, when a guest was out of the hotel or unavailable to take a call, we in the back office would type out a message which was then printed onto elegant A4 paper in triplicate. Two perforations in the paper would enable us to tear the paper into three. These identical messages would then be placed in three separate envelopes, one of which was left at the concierge desk, one left in the butler's main pantry on the second floor, while the third would be slipped underneath the guest's door. This meticulous process had been devised to ensure a guest never missed a message. Ordinarily, this wouldn't require too much effort. However, each time a call to the Royal Suite went unanswered, the caller would invariably request that, in addition to their message being left specifically for Miss Carey, in order to ensure she received it, the same message must also be left with every other member of her entourage. During her stay, Miss Carey's entourage was several members strong, with a single message having to be duplicated many times. Still, it certainly kept us on our toes!

Lastly, during one of the first few nights of Miss Carey's stay, she'd phone down to the back office and ask for the international dialling code for the US, to which I responded with 001. She'd do the same thing the following night and every other night that I took her call to which I'd respond with the same three digits, 001. Many years later, having become good friends with Daniel, the management trainee, and by then with both of us in our forties, he and I sat together one night and reminisced about our time at The Lanesborough. When it came to the subject of Mariah Carey, I happened to mention to him her habit of calling down each night and asking for the code to dial the US. With a wry smile, he then revealed that on his night shifts she'd do exactly the same thing with him!

Despite the temporary inconvenience of the hotel's more demanding guests, perhaps for the first time in my life, I began to feel a real sense of contentment. I'd never have imagined then that events would transpire to see me leave The Lanesborough by the middle of the summer. However, on account of those whose paths I'd soon cross, I'd come to realise that the summer of 1996 would see my adulthood begin in earnest. Who knows why we cross the paths of the people we do and how we can never know whether our lives really do change course or whether we remain on the course we were always meant to be on.

So, prior to my unintended departure during the summer, within the first three months of the new year, I'd cross paths with two people, both of whom would leave lasting impressions on me, albeit for entirely different reasons. The first would involve an altogether brief yet surreal encounter, while the other I'd meet unexpectedly one night at The Brief Encounter. With the Mariah Carey fiasco of eight weeks ago now something of a distant memory, Tristan would shortly redeem himself in my eyes in a way I couldn't possibly have imagined. Amid an atmosphere of febrile excitement and anticipation, on Monday 12th February, 1996, arguably the biggest star in the world checked into The Lanesborough.

For the purposes of this retelling, the magic actually began during my shift on the night before.

Having assembled as many of the night staff as he could in the back office, and clutching a memo from Sony Music Entertainment in his hand, Tristan read aloud. The memo revealed that our esteemed guest would be coming to London to receive a lifetime achievement accolade at

The Brits Awards show at Earl's Court on 19th February and would be staying at the hotel for just over a week. As Tristan read on, my mind began to wander, until he reached the part where the memo explained that our celebrated guest did not sleep well at night, and, curious as to the goings on behind the scenes, could often be found during this time wandering the back stairs and checking out the kitchens. This was definitely music to my ears and gave me hope that one night in the next week, while making my way down to the staff canteen, I might come face to face with perhaps the most enigmatic entertainer of our time. Alas, fate would not conspire in my favour, with my nightly forays downstairs for my lunch that week proving fruitless.

With Tristan having finished reading, the night team disbanded to their respective duties, and with my reports scattered about me, I began my night audit. Suddenly, the phone rang on my work computer followed by the name 'Lewis Wilson' which flashed up on the screen. It didn't escape my notice that the call came from one of the extensions in the Royal Suite. Picking up the phone, I was pleasantly surprised to hear the voice of my butler friend Richard on the other end. With a heady mix of excitement and astonishment in his voice, Richard said that he couldn't believe what the staff at Sony Music had done to the Royal Suite in preparation for tomorrow's big arrival and suggested I pop up and see for myself. Knowing I was unlikely to get another chance once our megastar guest had checked in the following day, I hurried upstairs to the Royal Suite for what would be the only time I'd set foot in there, to see for myself what it was that had Richard in such a tizzy.

As I mentioned before, the Royal Suite consisted of half of the second floor of the hotel, with views overlooking Wellington Arch and the gardens of Buckingham Palace. During my time there, the Royal Suite became a home away from home for senior American politicians, international recording artists and global CEOs. With my role being a primarily back office one, albeit with some guest interaction, I ventured to the guest's suites on the rarest of occasions. However, this was undoubtedly a special occasion and something for which I've remained grateful ever since, considering what I was about to witness. Having found my way to the main door of the Royal Suite, I opened it and went inside. Immediately to my right, sitting unplugged on a counter top in a little galley kitchen, was a Häagen-Dazs ice-cream machine. Unsure of where to go next, I followed the sound of pinging coming from one of the rooms. I soon found myself standing in the living area of the Royal Suite amid an array of exquisite flower arrangements which had been carefully placed around the room. Peering into one of sprays to take a sniff, I suddenly spotted bottles of fruit juice and small packets of M&Ms and Skittles hidden among the flowers. Just then, Richard called out and I found him in the room next door playing happily on a pinball machine. Creeping up behind, I flung my arms around Richard in gratitude at his having invited me to partake of this amazing spectacle. Having loosened my grip, I looked around me and realised I was standing in something resembling a sub-branch of Hamley's toy shop. While Richard continued to duel with the pinball machine, I marvelled at an enormous life-size metallic robot which stood motionless next to an equally large jukebox. Intrigued to learn of the musical tastes of our renowned guest, I took the liberty of thumbing through the selected albums to see if any of his own music were included. To this day, the album that I recall clearly, most likely on account of its peculiar cover art, was 'Jollification' by British rock band The Lightening Seeds.

Pausing briefly from his game, Richard suggested I take a look in the dining room next door. Upon entering, I noticed the long mahogany table and chairs I'd seen in the hotel brochure had been removed, to be replaced by a sea of stuff toys and the biggest teddy bear I'd ever seen. Anyone unaware of who would soon occupy this suite could be forgiven for thinking it was about to host the most magical children's party ever, not the man who had the biggest selling album of all time and who, two months prior, had bagged the UK Christmas number one spot with the eco-conscious anthem 'Earth Song', yet, when you're the King of Pop, you can clearly have whatever you want.

During the week that followed, the hotel was abuzz with excitement, both inside and out. Inside, anecdotes spread among the staff of their various interactions with the megastar, while at the rear of the hotel, a legion of loyal fans, dancing and singing to his music, kept a round-the-clock vigil, hoping to catch a glimpse of the global pop icon. Seizing the opportunity to make mischief, some of the more brazen among the hotel's butlers would go to a window of any available suite overlooking the assembled masses at the rear of the hotel and deliberately open the window and, in an attempt to obscure their appearance, deliberately pull the curtain around their face and wave excitedly to the fans. Inevitably, this would send them into an absolute frenzy, thinking it was their idol in a playful mood. A rumour circulated that a butler had actually donned one of the famed black fedoras and red military-esque jackets before pulling back the curtain and waving to the milling throng, sending them into near meltdown. How anybody in the accounts office, which looked out onto the forecourt at the rear of the hotel, got any work done that week, I'll never know.

As for the King of Pop having everything he wanted, there was one notable exception. One night during the week between his arrival and The Brit Awards ceremony, Hamley's closed their Regent Street branch one evening so he could shop in private. In the window that night stood a fabulous model of Disney's magic kingdom. With the model having caught Michael Jackson's eye, an enquiry was made as to whether the model was for sale. However, Hamley's staff advised that while it was not, they would gladly oblige and place an order for a replica to be made and then shipped to the Neverland ranch in California. As the tales from the staff of their various sightings and interactions with the King of Pop continued to unfurl, it became evident that the majority of my colleagues appeared to have had some dealings with him, with one among the notable exceptions being...me. That fact would also not escape Tristan's notice and his moment of redemption for the Mariah Carey brouhaha had come, on Michael Jackson's last night at The Lanesborough, which also happened to be the night of The Brit Awards.

That night, I arrived in the back office at my usual start time of 10pm and sat down next to my computer terminal, ready to answer the phones. As I began pulling off the report I used each night to check each guest's individual room rate, Tristan appeared at the door. Approaching, the table in front of me, he explained he was aware that I hadn't got to meet Michael Jackson. To rectify this, he asked if I would like to welcome him back to the hotel later that evening following his return from The Brit Awards. Stunned into silence by Tristan's suggestion, I barely muster my response before he told me to take my night audit down to the accounts office and begin it there and he would cover the phones.

With fumbling fingers, I gathered up my audit and hurried down to the accounts office on the ground floor, which looked out the forecourt at the rear of the hotel. As I turned the corner and approached the accounts office, I could hear the sound of the fans outside, chanting and singing along to his music playing on a ghetto blaster. As I pulled back the net curtain covering one of the sash windows, I peered out and saw some of the fans breakdancing to the music. It was far too noisy, and far too exciting an atmosphere to even consider doing my audit, so, I just sat back and enjoyed the spectacle unfolding before my eyes and it wouldn't be too long before the man of the moment arrived back. Outside the door to accounts, members of the hotel security team had assembled and were in constant contact via radio with the Jackson security team. I popped my head out the door of accounts and told the security guards that Tristan had asked me to welcome Mr. Jackson back to the hotel to which they replied that his ETA was approximately five minutes. Instead of returning to accounts, I remained with the security guards on the inside of the main door. Although my view out onto the forecourt was obscured by the net curtai covering the door, I could tell his car had pulled up the moment that, all of a sudden, the crowd unleashed a mightily thunderous roar. Reminiscent of a football match, the controlled chaos continued for as long as the King of Pop remained outside, greeting the multitude of loyal fans who'd braved the chilly February temperatures in the hope of meeting him, and he had not disappointed them. All of a sudden, a thin man, a little taller than me at no more than about 5 feet 10 inches, walked with purpose through the door. My eyes fixed firmly on him as he ventured in my direction, I wanted to take in as much of his image as I could to ensure that such a brief moment in time remained vivid in my memory before my eventual ageing would cause the rich detail to fade. Wearing tight-fitting black trousers and a military style black jacket, his clothing accentuated his pale complexion. I was struck by how thin he was and the angular formation of his eyebrows, suggesting they'd been shaped and pencilled or tattooed on. Upon reaching me I smiled and spoke aloud, welcoming him back to The Lanesborough. As he passed me, I looked down at the Brit award figurine clutched firmly in his hand. Having reached the same corner I'd turned earlier before going into the accounts office, he turned to face me, raised his hand to his head, smiled and then saluted. He turned the corner and then disappeared.

Oblivious to the fact that there was more to come that night from the King of Pop, I settled down in the back office and got on with my night audit. While working through my room rate report, I became aware of something I'd never heard at The Lanesborough, before or since, in the form of raised voices in the hotel lobby. My curiosity roused, I stood at the entrance to the back office and saw two burly African-American men involved in a tense exchange of some kind about who should have done this and who should have done that. At that moment the phone rang. I picked it up and on the end of the line was a lady who stated she was calling from Earl's Court. She explained she knew Michael was staying at the hotel and, while fully appreciating that I couldn't put her through to him, she asked whether I could get a message to him saying that he sang like an angel. While in truth that was impossible if I wanted to remain in a job, I didn't have the heart to say no outright and advised the affable lady I would try my best. With this, she offered her thanks and told me how lucky I was to be working in the hotel where Michael Jackson was staying. She then made a comment about someone jumping on the stage during Michael Jackson's act and then hung up. With the furore in reception having died down and having hardly made any dent in my audit, I spent much of the remainder of the night playing catchup.

That is, until around 6.30am, when an internal call came in and the name 'Lewis Wilson' and the number 220 flashed up on my computer screen. Extension 220 belonged to the private phone in the bedroom of the Royal Suite, with Lewis Wilson the pseudonym of Michael Jackson. The heat was back on and I felt the same surge throughout my body as I had the night I'd taken Mariah Carey's hefty food order. However, this time the caller's voice sounded calm, quiet and unassuming, although peculiarly high-pitched...and unmistakably him. Beginning in a concerned and surprisingly informal tone, Mr. Jackson asked if I'd seen the news that morning. I replied that I hadn't as I tended not to read the papers although I said I was aware that the day's papers had indeed arrived. He went on to explain how he'd been made aware after finishing his rendition of 'Earth Song' that during the performance, someone had jumped up on the stage in an attempt to disrupt his act. He continued by saying he was also told that in the process of jumping up on the stage, the man had knocked some of the children off and that they had been injured. He expressed his concern, stating he wanted to check on their welfare and, while he did have a contact number for one of the families, every time he dialled the number the phone went “beep”. In order to try to help him, I asked Mr. Jackson for the number so I could test it for him, to which he read the number back to me. Having then studied the number, I soon realised he was a digit short. Although desperate not to disappoint him, I explained that there was no way of knowing the number of the digit which was missing and where in the sequence of numbers it fell. Offering him my sincere apologies, I advised that there was nothing more I could do. Nonetheless, in a calm and composed manner, he thanked me for my explaining the situation to him.

I wish I knew how to account for what happened next and what made me say what followed. Maybe it had something to do with what I'd seen in the Royal Suite, or hearing his concern for the allegedly injured children, or the fact that he seemed, and sounded, very childlike himself, but for some unknown reason I seemed intent on expressing my empathy with him. Just then, I asked him if I could say something to him. Responding in the same gentle manner as before he replied that I could. With this, I blurted out that while I couldn't relate to the kind of childhood he'd had, I understood how it felt to have your childhood taken away from you and how that feeling would remain with me for the rest of my life. In the brief silence that followed I could feel my heart beating hard in my chest, to which he provided my relief when he offered perhaps the most genuine and heartfelt “thank you very much” I've think I've ever received. With the Piccadilly line that morning temporarily suspended, I took the bus back to Hammersmith. Sitting at the back, I reflected on how surrealness of the last ten hours and just wanted to tap any of my fellow passengers on the back and tell them what had just happened, but I didn't. They probably wouldn't have believed me, anyway.

While stories of Michael Jackson and Mariah Carey et al may make for compelling tales to tell, what made The Lanesborough truly special was the people toiling away behind the scenes. They were the ones who really made magic happen. Chief among them were the hotel's courteous, professional and patient butlers, who catered to each guest's every whim, no matter how outlandish the request and wouldn't hesitate to answer a call to a guest in the bath who felt it was the butler's job to turn on the cold tap because the bath water they were in was too hot, or the unassuming group of Polish cleaners dressed in navy blue boiler suits, no socks and the kind of black plimsolls we used to wear for PE at school. They worked like trojans night after night to keep the hotel clean and appeared to take great pride in scrubbing the corners of the downstairs corridors with toothbrushes, and none of them ever spoke a word of English. Then there's was the highly efficient security staff, who kept us and the hotel guests safe. Everybody did their best, sometimes in the face of considerable provocation and ingratitude, to provide the best service in the world. Like theatre, what's going on behind the scenes can often be far more interesting than what's happening on stage and the back stories more compelling, exciting and representative of a life well lived.

So, by now it was March 1996 and, following a chance meeting at The Brief, I would leave The Lanesborough in June of that year, and the UK itself a month later. I'd find myself on a new adventure that would change my life and either make or break me. Oh and every time I see a bird of paradise or smell that luscious, heady scent of fresh lilies, I'm immediately transported back to The Lanesborough, although I wonder whether it was all just a dream.

Descending the stairs leading from the upper to the lower bar of The Brief Encounter that March night, I heard Orlando the DJ calling out over his microphone for a cork. Situated at 42 St. Martin's Lane, just up from Trafalgar Square and set out on two levels, 'The Brief' had the dubious reputation of being 'one step up from a toilet'. Presumably that was on account of the dinginess of the lower level, where I preferred to be. This was not for any kind of seedy sexual gratification but because the downstairs bar housed the DJ's booth and was also where my casual friends tended to gather. While 'You Spin Me Round' by Dead or Alive began to play, I handed over my coat to the cloakroom attendant before grabbing a drink at the bar. Intrigued as to why Orlando had called out to the bar for a cork, no sooner had I reached the DJ booth than I understood why. Having realised I'd just walked into a fart cloud, I asked Orlando if he was the miscreant. Quick to exonerate himself, Orlando explained that he'd just been talking to “some old judge” who'd decided to drop one at the DJ booth before leaving. As 'You Spin Me Round' faded out, Orlando exclaimed, much to the amusement of the other revellers, how the fart had “spun him round” and that he “could still smell it”.

Giggling to myself as I left the DJ booth, I soon found my friends and was pleasantly surprised by the presence of two new members. By coincidence, two chaps among our group had friends visiting them, both Americans, and had decided to bring them both to 'The Brief' on the same night. Although strangers to each other, both men were soon engrossed in conversation and took little notice of the rest of the group. The taller of the two had his back to me, while the other, a handsome dark-haired chap around my age, stood facing me. Catching up with my friends, we began discussing the terror of the Dunblane massacre that had occurred earlier in the week in which a teacher and sixteen of her pupils were shot dead while fifteen others were injured. Just then, the taller of the two men turned around and looked at me. Waiting for a suitable moment to interject, he asked me if I'd recently been up in Scotland. I replied by saying that I'd never been to Scotland and that I must have a double. Introducing himself to me as Warren, he agreed and explained that he'd just met this so called double during a short trip to Scotland. Despite only having just bought a drink, he asked me if I wanted another. From there our conversation began and an exchange flowed freely. Warren revealed that he was thirty-five years of age and from Fort Worth in Texas. Being a leggy 6'2”, Warren was considerably taller than me and also twelve years older. A dark-haired and not at all unattractive man, he came across as polite and well-mannered. However, I found the other American, a fellow named Paul, the more attractive of the two and remarked to Warren how deep they appeared to have been in conversation. To this, Warren explained that he and Paul had been discussing the possibility of reversing a circumcision. To my enquiry into his knowledge on the subject, Warren revealed that he was on a study year abroad as part of his undergraduate degree with the St. George's School of Medicine in Grenada. Having spent the first part of his third year at Poole Hospital in Dorset, he was now based at the North Middlesex Hospital in Edmonton, North London. To the disclosure that he'd taken a room in shared accommodation on Broadwater Road in nearby Tottenham, I explained to Warren the notoriety of that particular area following the Broadwater Farm riots eleven years earlier. At this, Warren scoffed, revealing that as a paramedic in Fort Worth he'd witnessed, and been involved in, far worse.

Finding Warren's self-assuredness and good manners alluring, he and I began spending as much of our spare time together as we could. I didn't really delve too deeply at that time into what we had in common, although we'd later indulge our mutual love of tennis whenever we could. It didn't escape my notice that we dressed very differently. Having been swept up in the seventies revival in the early to mid 90s, in addition to my cherry red DMs and white jeans, I regularly wore wide-legged trousers with Cuban heel boots and fitted shirts. Despite this look being a common sight in London at the time, when Warren and I began going out to the bars he'd be openly critical of my dress sense, referring disparagingly to my outfits as “disco fever”. My look contrasted sharply with his more conservative button-down 'Polo' by Ralph Lauren shirts, blue jeans and Timberland boots. What my naivete prevented me from realising at the time was that Warren's casual put-downs betrayed something darker in his character, something which would reveal itself to me fully before long.

In the meantime, and much to the chagrin of Warren's housemates at Broadwater Road, I began to sleep over regularly during my nights off. The inevitable fallout from this led to Warren and I moving in together, first of all renting a converted loft from a couple in Wood Green in North London. Then, in June, once Warren's internship at North Middlesex University Hospital had ended, he expressed a desire to return to the south coast and within a matter of a few weeks we'd moved to Southsea, in Portsmouth.

During our brief stint in Southsea, Warren received word from St. George's University advisinghim that if he hoped to secure a graduate post, he'd stand a better chance by applying while completing his fourth year back in America. Returning home one afternoon from the temp job I'd undertaken to be met with the news, I automatically thought Warren would be heading back to America alone. Unable to hold back the tears, I began to cry. To my surprise, Warren explained that he wanted me to go with him. As certain as I could be of my affection for him and having concluded that if he didn't feel the same way about me, he wouldn't have asked me, it felt like the right thing to do to go with him. So, we set about planning the next steps in our future. While Warren began frantically applying to various U.S. hospitals for a placement to complete his year four studies, I secured a visitor's visa which would allow me to stay for an initial period of twelve months. With Warren having successfully gained a post at University Hospital in Newark, New Jersey, on Friday 26th July, 1996, we landed at Newark International Airport where we spent the night at one of the airport hotels.

Making good use of their connections, prior to us leaving the UK, Warren had contacted his father, Warren Sr, and his mother, Kitsy, (which she preferred to her real name, Katherine) for help finding somewhere to live in New Jersey. Warren's father was a minister in the Presbyterian church of Fort Worth and a fellow minister with whom he'd worked had transferred to the ministry covering the Newark diocese. As luck would have it, a recently refurbished house attached to the Second Presbyterian Church located in downtown Newark on the corner of Washington and James Street remained empty and may be available for our short-term use. Warren Sr had arranged for us to meet a lady named Carrie Washington at the house in Newark the following day. Unsure of exactly how to get there, Warren asked a room service waiter at the hotel for directions to which he replied that nobody goes downtown unless they really have to! Despite those foreboding words and weary from our long journey, Warren and I slept soundly that night, huddled on one side of the most enormous bed I'd ever seen. The next morning, my apprehension would be roused when we awoke to news that a bomb had been detonated overnight at the Olympic Park in Atlanta, Georgia.

The real cause of my unease was the fact that the next day, Sunday, Warren was booked to fly from Newark down to his home in Fort Worth. The idea was to fly down to Texas and retrieve his personal effects stored with his parents, collect his Honda Accord car then drive the sixteen-hundred miles back to Newark, arriving sometime the following Friday. This meant me potentially staying alone in a house I didn't know in a city seemingly considered too dangerous in which to set foot. Voicing my concerns to him as we headed in a hire car downtown, Warren told me not to worry and that he had a plan. Feeling less than reassured, I found the sight of several pairs of Converse sneakers tied at the laces and dangling from the telegraph wires stretched across the residential streets leading into downtown a curious albeit temporary distraction. Our destination, the Second Presbyterian Church of Newark, lay on the corner of Washington and James Street and, having pulled up outside the first house after the church on James Street, there waiting for us was our contact, Carrie Washington.

Standing on the steps of the three-story brownstone at number 19, Carrie, with her full set of luminous white teeth, greeted us enthusiastically before unlocking the front door. The door to this house was unusual in that, apart from a brown metal trim and central bar, it was full glass through which you could see from the street into every room on that floor. What I instantly noticed from the steps I would also observe on the two upper floors, that the house, although clearly recently renovated, contained absolutely no furniture whatsoever. Warren had arranged for a removal van to transport the bulker items among his belongings, including his bed, from Fort Worth to Newark, although delivery would not be until the end of the following week. With Warren in agreement that the house would be ideal and Carrie similarly pleased that we'd be staying, 19 James Street looked set to be our new temporary home. Carrie's warmth towards us had taken me somewhat by surprise, having initially thought that most American's of faith were automatically prejudiced against homosexuals. Warren's disclosure to me that in their spare time his parents judged drag shows coupled with Carrie's friendliness towards us led me to challenge my own pre-conceived ideas on this matter.

To Warren's aforementioned plan to help me through the next five days, while he'd come good on his plan, he'd do so in a way I hadn't expected. Assuring me that I wouldn't be alone during his absence, no sooner had we left James Street than we pulled up outside a warehouse type building which was home to the Humane Society of Newark. Unlike Warren, I hadn't considered us adopting a dog but before I knew it we were peering into metal cages stacked several high, with equally inquisitive faces staring back at us. With each one appearing more frightened and desperate than the last, I found myself beginning to well up. Just then, Warren turned around from one of the cages further along and asked about the dog with ears like a bat. Having joined him, I peered into the cage and looked straight into the eyes of a trembling brown and white Jack Russell, which sported the kind of deer-like ears that were completely out of proportion to the rest of its body. With its head bowed down yet looking up, it was clear our little friend was more uneasy in its surroundings than I'd been at James Street earlier. So, rather than getting a dog for my protection, Dee Dee, as we later learned was her name, ended up with me for hers.Stopping by a local supermarket, we grabbed enough by way of groceries and dog food to see us through until Warren's return the following week. With Dee Dee firmly ensconced between us, we went to sleep on the top floor of number 19 that Saturday night without the need for any blankets, courtesy of the sultry July heat. Although I more than likely imagined it, I swear I could hear the sound of gunshots in the distance each night.

Without doubt, the best thing about our brief stay at the church house on James Street was meeting our charismatic neighbour at number 21. Epitomising the blonde-haired blue-eyed all-American stereotype, Ingrid was a law student at the Newark campus of Rutgers University, a few blocks away. Notwithstanding her academic abilities, Ingrid's charm lay in her love of life, her infectious laugh and, most importantly, her compassion for others. Meeting Ingrid and her boyfriend, Regis, during that first week at the house, we hit it off instantly. With Ingrid already the proud mum of a pound dog herself, a black 'Toto' type terrier by the name of Lennie, Warren and I won plaudits from Ingrid for having adopted Dee Dee, who Ingrid in turn adopted as her own. Having Ingrid nearby during Warren's absence reassured me and a few times that first week I found myself climbing out of the kitchen window on the first floor of number 19 onto a flat roof and then in through Ingrid's kitchen window at number 21 to share a Chinese takeaway. We'd also take it in turns to feed a homeless man named Joseph, heavily clothed despite the oppressive July heat, who'd climb up onto the flat roof and stop by our respective windows for some food and a chat. This would all come to an abrupt end one afternoon approximately three weeks later when Warren received a call from Carrie to ask if he and I were a couple, With Warren then confirming that we were, Carrie explained that we could no longer stay in the church house and asked us to move out as soon as possible. So, for the next three months, Warren, Dee Dee and I lived in a three story townhouse on a new development on the other side of Newark, in a rather posh sounding area called Society Hill.

Perhaps it was just as well that during our time in Newark I remained unaware of the fact that between 1990 and 1995, the city had the third highest average yearly violent crime rate in America. While a hive of corporate and academic activity during the day, downtown Newark at night resembled a ghost town. Regardless of our direction of travel, leaving and entering the city always involved driving through neighbourhoods blighted by poverty and deprivation. A few months later, along with my friend Daniel from The Lanesborough, Warren and I drove through Detroit en route back from Niagara Falls. Having left The Lanesborough too, Daniel had come to stay with us for a few weeks before setting off on a three month North American tour. As we made our way through Detroit, the forbidding sight of seemingly endless decaying buildings roused within me the same sense of soullessness and despair I'd experienced in Newark. However, being in such close proximity to New York City had its compensations and with Warren at the University Hospital during the day, I'd take the opportunity as often as I could to ride the PATH train from Newark to New York for a dollar and spend the day wandering around Manhattan. On the other hand, it wasn't all play as I had an important objective to fulfil if Iwanted to stay in America and, fortuitously, I had Daniel on hand to help me.